Poirot says he doesn’t shy away from controversial topics, though he does not like to criticise others. “What the Bible says about a certain issue, I will talk about,” he says. He says when he made a video talking about “how the devil uses certain songs” to “degrade our culture” he was widely mocked by Satanists and atheists. Poirot, Phillips and Ashraf have all had videos removed by TikTok in the past, although some have been reinstated after an appeal. TikTok removes videos that violate its community guidelines, which ban hate speech, hateful behaviour, sexually explicit content and misinformation, among other things, although the app has only recently begun specifying which rule a user has broken when a video is removed.

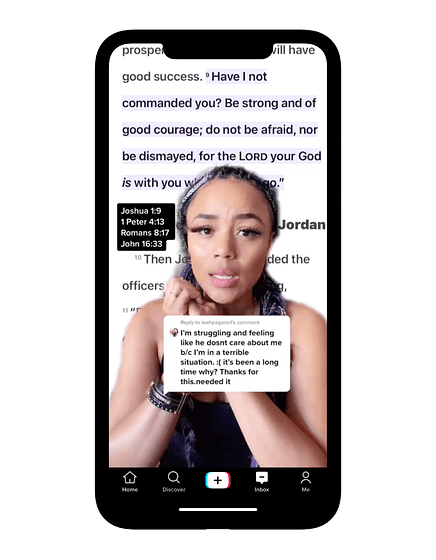

All of the religious TikTokers in this piece have also experienced hateful comments and trolling. Jacobi says she also had neo-Nazis sending her bomb threats on other social media channels after she made a TikTok video about Jewish stereotypes. “There are such highs and such lows,” she says of creating religious content on TikTok. “It’s a whirlwind and it’s exciting and it’s terrifying, truthfully.”

So will those two billion TikTok views truly shift the religious landscape in a meaningful way? Many who view religious content on TikTok are already religious, so a huge number of views does not necessarily equate to shifting attitudes. Cheong says it is too early to tell whether the popularity of religion on TikTok is ephemeral. She also says that some may be troubled by the fact many religious TikTokers don’t have formal theological training and therefore might misrepresent their religion. This is a concern shared by Stewart M Hoover, a media and religious studies professor at the University of Colorado.

“Charismatic religious leaders have led many people into negative and dangerous things in the past. And in the online environment, there aren’t the usual guardrails and sanctions, so anything can happen,” he says. But Hoover doubts whether TikTok will truly transform the religious landscape long-term, arguing that making religion accessible online has a “double edge” as the content can turn people off. He also adds that traditional religious authority has a lesser role on TikTok.